Que scripsit scripta,

sua manus sit benedicta.

Anno domini M°CCCCC°xxiiij scripsi ego, soror Cecilia Hughen, hunc librum cum fauore venerabilis domine nostre A R, anno etatis mee XXIII°.

Que librum istum post obitum meum possederit, oret amore Ihesu et Marie pro scriptrice Aue Maria Requiem

(Stuttgart, Landesbibliothek, Cod. brev. 22, 419v)

“May the hand of her who wrote this text be blessed.

In the year of our Lord 1524, I, Sister Cecilia Hüge, wrote this book with the favour of our venerable Domina A[nna] R[oden], at the age of 23.

Whoever possesses this book after my death, may pray for the love of Jesus and Mary a Hail Mary and Requiem for the female scribe.”

(Stuttgart, Landesbibliothek, Cod. brev. 22, fol. 419v)

In 1524 – exactly 500 years ago – Cecilia Hüge, nun and later prioress of Neukloster Buxtehude, completed her prayer book, as recorded in the manuscript’s closing lines on fol. 419v. The small but fat prayer book (419 folios of 17.5 x 12 cm, about postcard size) includes Latin and Low German texts for the period from Holy Saturday to the fifth Sunday after Easter. These texts, based on the liturgy of the Divine Service, explaining and expanding it, were meant for the personal devotion of individual nuns. The volume, now held in the Landesbibliothek Stuttgart (Cod. brev. 22), is currently the only prayer book definitely attributed to Neukloster Buxtehude via its colophon. The former Benedictine convent was founded in 1270 in Neuenkirchen, relocated to Buxtehude in 1286 and remained active until 1705/1707.

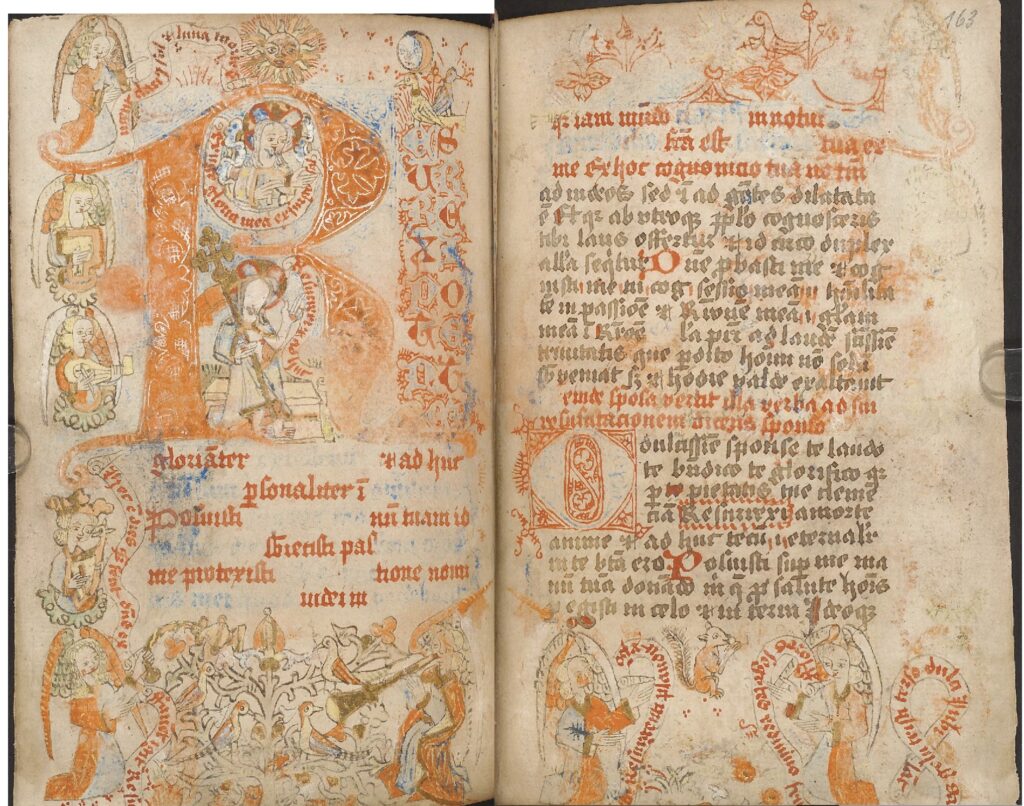

So far, the volume has fallen through the cracks since it is too late to be discussed as “medieval manuscript” but does not conform to the narrative of Renaissance art, following earlier models of book production. But it has its own, highly distinctive style. The double-spread (162v–163r), for example, shows a theologically complex composition of text, historiated initial, colourful marginal illuminations and scrolls commenting on the events on the page like speech bubbles in a graphic novel. In the R initial, God the father (upper compartment) calls upon God the son (lower compartment) to rise – and Christ follows the call, saying (both in his speech bubbles and in the text proper) RESURREXI (I have risen!). Above the initial, sun and moon join in the celebration, with an angel explaining their presence with a line from the sequence ‘Laudes Salvatori’ which was sung on Easter Day. A host of other angels make a merry noise with a variety of instruments, as does David with his harp and a whole flock of birds – and a squirrel! Even though the volume has suffered badly through water damage which washed out most of the blue text and it only used a limited number of colours, the celebratory mood is still vividly conveyed.

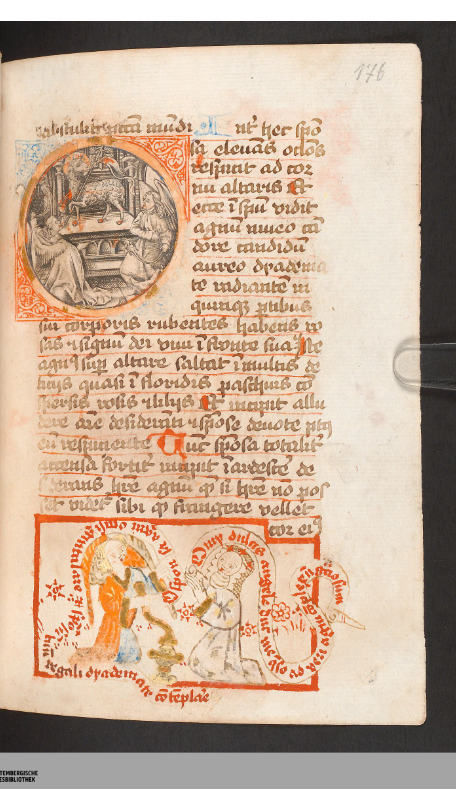

Cecilia crafted her prayer book as a versatile tool for deepening her relationship with the Divine. Reflecting this purpose, the Buxtehude nun herself appears in the marginal illumination, such as on fol. 176r where she implores her guardian angel to lead her to the lamb of God, her bridegroom Christ. Notably, the same folio features a cutting from an as-yet unidentified engraving of the lamb of God on the altar adored by two angels, illustrating the body of the text and linking to the prayer of the nun below.

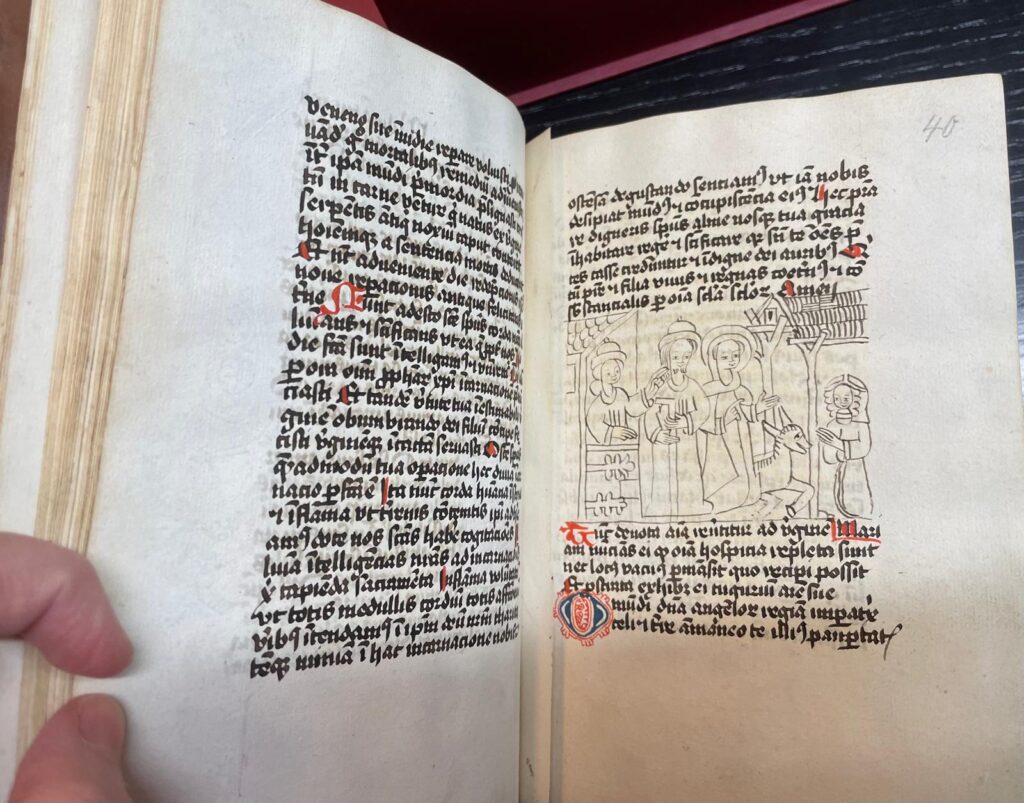

A comparison of this distinctive illumination style with other manuscripts suggests the existence of a small corpus of bilingual prayer books likely produced in the Benedictine convent. Initial archival and library research points to Ms. 729 in the Cathedral Library in Hildesheim as another manuscript belonging to this corpus. The manuscript is a Christmas side-kick to Cecilia’s Easter prayerbook, with approximately the same size and shape. It has similar colourful initials but only one marginal illustration which is only an ink drawing without colouring-in. But this illustration has a truly unique topic: Mary and Joseph, searching for shelter, are sent from an inn-keeper to a stable on the right-hand side. A donkey is leading the way – and is encountering a nun, kneeling in a similar way to the one in Cecilia’s manuscript, who has catapulted herself into Bethlehem. Here she offers her soul as alternative accommodation.

The Latin text below the drawing explains (fol. 40r): Tunc deuota anima reuertitur ad virginem Mariam, nuncians ei quod omnia hospicia repleta sunt, nec locus vacuus permansit, quo recipi possit. Et prostrata exhibet ei tugurium anime sue (Then the devout soul returns to the Virgin Mary, announcing to her that all the inns are full, and no empty place remains where she can be received. And kneeling down, she offers her the shelter of her soul.)

There is much more to explore in these manuscripts which bridge the medieval and the early modern, giving a vivid insight into how female devotion shaped mystical thinking about Christian topics – compare the text to Martin Luther’s hymn ‘Vom Himmel hoch’ where the devotee concludes with ‘Ach mein herzliebes Jesulein, mach dir ein rein sanft Bettelein, zu ruh’n in meines Herzen Schrein…’ (O dearest Christchild, make yourself a pure soft little bed to rest in the shrine of my heart…). This blogpost is starting point for further investigations into the corpus. Updates on further findings will be posted on the Medingen blog.