The ‘Song of Songs’ in Medieval Female Communities

Lecture for the Training Group ‘Autonomy of Heteronomous Texts in Antiquity and the Middle Ages’

At the start of the ‘Song of Songs’, the choir of the young women sing ‘Draw me after you, and we will follow’ (Chorus Adolescentularum: Trahe me, post te curremus, Ct 1:2) which is a line that is taken up time and again in medieval song, meditation, and prayer, particularly in female religious communities. This was despite – or perhaps even because – the ‘Song of Songs’ was not only one of the most influential but also one of the most controversial texts in the Middle Ages. The poetic love dialogue attributed to king Solomon is the only biblical book where there is no literal sense possible; even in the Jewish tradition there is already an inherent need for a commentary to explain the allegorical reading which then forms the basis for all medieval engagement with the text. The lecture proposes that the importance for medieval female communities is precisely in the intersection of erotic and allegorical aspects.

The analysis follows the creative engagement with the Song of Songs commentary tradition in Latin and vernacular literature from Williram von Ebersberg’s commentary (11th century) and the ‘St. Trudperter Hohelied’ (12th century) and mystics such as Mechthild von Magdeburg (13th century) to the wide variety of responses in devotional texts, images and music in the 15th and 16th centuries.

The main focus will be on the bilingual writing of the Northern German nuns from the Cistercian Abbey of Medingen with a final look at ‘Herr Christ der einge Gottssohn’, a hymn written in Wittenberg in 1522 by the former nun Elisabeth Cruciger, née von Meseritz, and printed in the first Protestant hymnbook in 1524, showing how bridal mysticism based on the Song of Songs commentary tradition from the convents shapeshifts in Reformation theology.

1. Williram of Ebersberg: Expositio in Cantica Canticorum

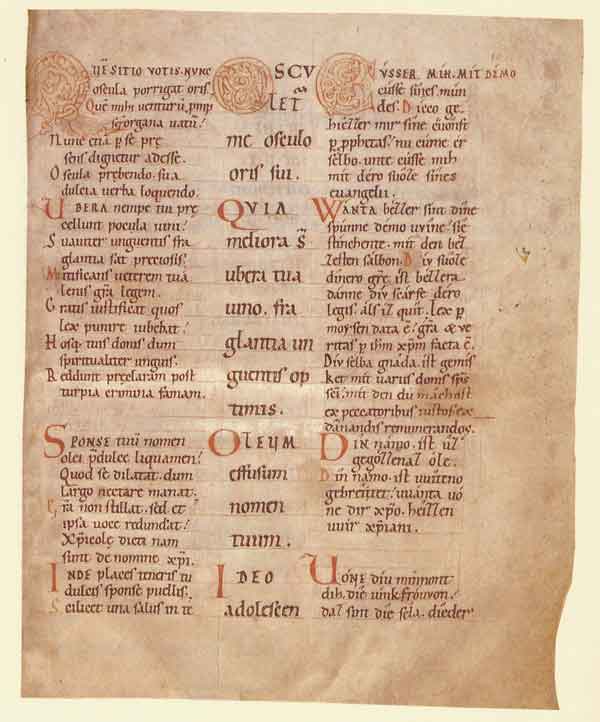

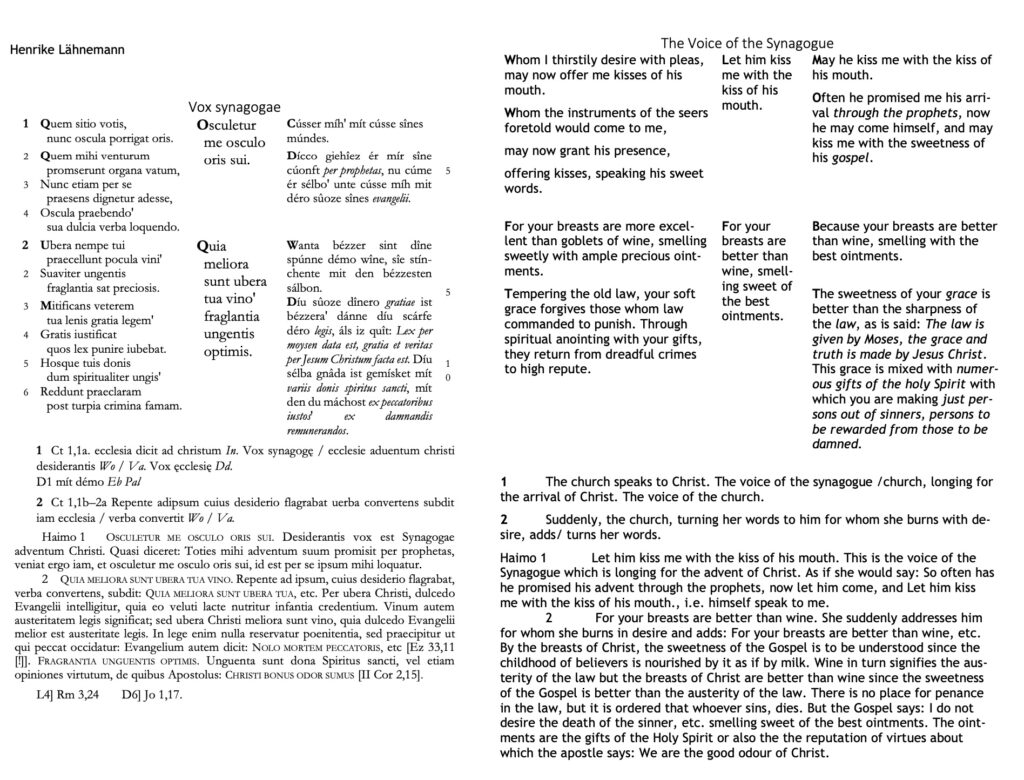

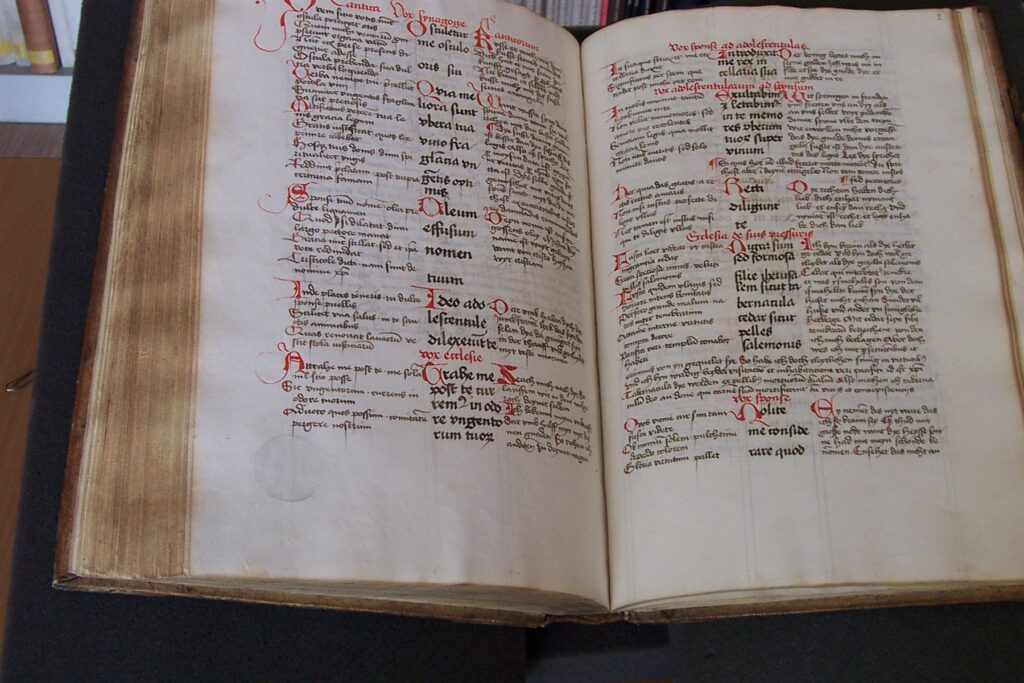

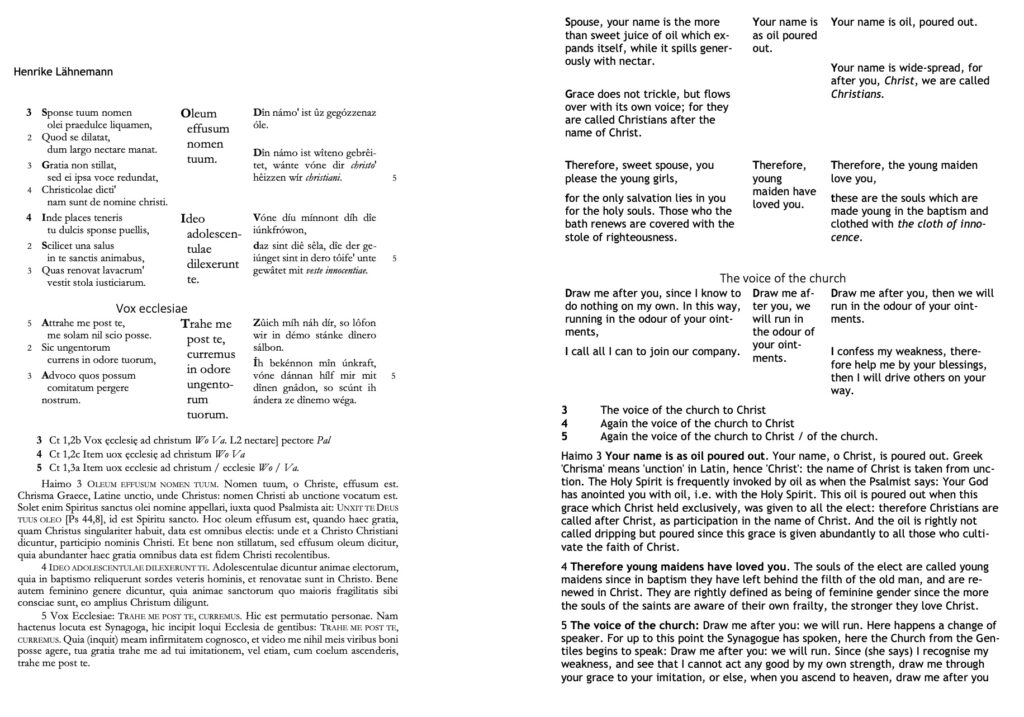

The Benedictine abbot Williram of Ebersberg (died 3 January 1085) wrote his commentary on the Song of Songs based on the 9th century commentary by Haimo of Auxerre but transformed it completely by rendering it in Old High German prose and Latin verse as an ‘opus geminum’, a twin commentary. His translation was transmitted continuously in the Middle Ages, e.g. in a copy written in 1523 for the Dominican nuns of Heilig Kreuz in Bamberg (see figure 2).

Along the way, it inspired other vernacular readings of the Song of Songs such as the ‘St. Trudperter Hohelied’, based on Williram’s German translation. Much of the work’s appeal lies in its complex layout, in which the Vulgate text, vernacular translation and prose commentary, Latin verse paraphrase and verse commentary are arranged in 150 sections in a five-part structure: the Vulgate in the middle column in larger letters, the Latin verse in indented lines in a left hand column, and the German prose in a right-hand column. Williram describes this in his preface being ‘like a body positioned in the middle, girded by those [verse and prose explanation] on both sides’. This language of the text as ‘body’ is parallel to that used when speaking about the bride of the biblical dialogue, whose different body parts are praised for their beauty and the ornaments of her dress. Our essay argues that Williram developed his commentary on the Song of Songs into a unity of text, visually powerful layout, and commentary in the form of direct dialogue, and that over the centuries this aesthetic potential was realized anew in each materialization of the text on parchment and paper. Every manuscript of the Expositio presents the text in its own way and is an expression of a specific manuscript culture.

Preface (in rhyming prose)

Highlighted in bold are the rhyme words. The ‘ (breathing mark) indicates original punctuation marks in the oldest two manuscripts (see figure 1), indicating pause or rhyme. The left-hand side text is based on the German edition Michael Rupp and I did in 2004 for de Gruyter (Williram von Ebersberg: ›Expositio in Cantica Canticorum‹ und das ›Commentarium in Cantica Canticorum‹ Haimos von Auxerre), the English translation is work-in-progress for our planned English edition – corrections welcome!

Incipit Praefatio Willirammi Babinbergensis Scolastici’Fuldensis monachi’ in Cantica canticorum. | A prologue by Williram, Scholar at Bamberg, Monk at Fulda, for the Song of Songs: |

| Cum maiorum studia intueor’ quibus in divina pagina nobiliter floruêre, cogor huius temporis faeces deflere, cum iam fere omne litterale defecit studium, solumque avaritiae’invidiae et contentionis remansit exercitium. Nam et siqui sunt qui sub scolari ferula grammaticae et dialecticae studiis imbuuntur, haec sibi sufficere arbitrantes’ divinae paginae omnino obliviscuntur, cum ob hoc solum christianis liceat gentiles libros legere, ut ex his quanta distantia sit lucis ac tenebrarum’ veritatis et erroris possint discernere. | When I consider how our predecessors brought the study of Holy Scripture into noble flowering, I must bemoan the vileness our time, where even basic study skills are lacking, the only training remaining being in avarice, envy and controversy. Even if there are some who through school discipline have been induced to study grammar and dialectics, they regard this as sufficient and completely forget Holy Scripture, although the only reason for Christians to read gentile books should be to appreciate the huge difference between light and darkness, truth and error. |

| Alii vero cum in divinis dogmatibus sint valentes‘ tamen creditum sibi talentum in terra abscondentes‘ caeteros qui in lectionibus et canticis peccant derident‘ nec imbecillitati eorum vel instructione vel librorum emendatione quicquam consulti exhibent. | Others who are capable of understanding divine dogmatics are, however, hiding the talent given to them in the earth and scorn those who make mistakes in reading and chanting instead of assisting them in overcoming their weaknesses by instructing them or revising books for them. |

| Unum in francia comperi’ Lantfrancum nomine antea maxime valentem in dialectica, nunc ad ecclesiastica se contulisse studia‘ et in epistulis pauli et psalterio multorum sua subtilitate exacuisse ingenia. Ad quem audiendum cum multi nostratum confluant‘ spero quod eius exemplo etiam in nostris provinciis ad multorum utilitatem industriae suae fructum producant. | I know of someone in France, called Lanfranc, who at first specialised in dialectics but has now turned to church-approved studies and through his subtle understanding sharpens the minds of many on the epistles of Paul and the Psalter. If many of us join to hear him, I hope that his example will also bear fruit in our regions. |

| Et quia saepe contingit’ ut impetu fortium equorum etiam caballi ad cursum concitentur, quamvis segnitiem ingenioli mei non ignorem‘ deum tamen bone voluntatis sperans adiutorem‘ decrevi etiam ex mea particula studioso lectori aliqua emolumenti praebere adminicula. | And since it happens quite often that the impetus of racing horses spurs even pack animals into galloping, I have decided – though I know all too well how slow my little mind works – to prepare from my scattered knowledge bits of advice for industrious readers, trusting in God who helps those who mean well. |

| Itaque Cantica canticorum quae sui magnitudinem ipso nomine testantur’ statui si deus annuerit et versibus et teutonica planiora reddere, ut córpus in medio positum’ his utrimque cingatur‘ et ita facilius intellectui occurrat quod investigatur. De meo nihil addidi, sed omnia de sanctorum patrum diversis expositionibus eruta in unum compegi, et magis sensui quam verbis tam in versibus quam in teutonica operam dedi. Eisdem versibus interdum utor, quia quae spiritus sanctus eisdem verbis saepius repetivit, haec etiam me eisdem versibus saepius repetere non indecens visum fuit. Expositionis tenorem sponso et sponsae sicut in corpore sic in versibus et teutonica placuit asscribi, ut maioris auctoritatis videatur, et quivis legens’ personarum alterna locutione delectabilius afficiatur. Nescio an me ludit amabilis error’ aut certe qui Salomoni pluit’ mihi etiam vel aliquantulum stillare dignatur, interdum mea legens’ sic delectabiliter afficior’ quasi haec probatus aliquis composuerit auctor. Opusculum hoc quamdiu vixero’doctioribus emendandum offero, siquid peccavi’ illorum monitu non erubesco eradere, siquid illis placuerit’ non pigritor addere. | I have therefore decided to tackle the ‘Songs of Songs’, where the excellence is reflected even by its name. I shall – God willing – make it more accessible in both verse and German so that the body in the middle is fortified on either side, and the mind can thus grasp more easily what it discussed. Of my own, I have added nothing but collected everything I unearthed from several expositions of the holy fathers, and I have in the verse as well as the German put greater stress on the sense than on the words. Sometimes, I use the same lines again since it did not seem improper to repeat what the holy Ghost had repeated with the same words several times with the same lines several times. It seemed advisable to assign – as in the body of the text – the voice of the commentary to spouse and bride, both in the verse the German, so that the explanation may have greater authority, and touch every reader by the alternation of the speakers. I am not sure whether I am deluded by an amiable error or whether He, who made it rain over Solomon, honoured me with some little drops, since sometimes I am so pleasantly touched by reading my own as if it had been composed by some practised author. As long as I live, I offer this little book for emendation to the more learned: if I did anything inappropriate, I will not blush to erase it; if they plead for anything, I am not ashamed to add it. |

2. St. Trudperter Hoheslied

The St. Trudperter Hoheslied was written in the 12th century for nuns; the text is based on the edition by Friedrich Ohly, translation my own.

| Prolog (Zweiter Werkeingang) | Second Prologue |

| 6Wir haben vernomen von deme heiligen geiste, wie er kôsete durch den wîsen Salomônem, daz er wunschte eines starken wîbes. dar nâch begunde er singen cantica canticorum. nû sehen waz daz sanc sî. ez ist sanc aller sange. ez ist ouch sehen der gesiuneclichen tugende. ez ist ein weide der inneren sinne. ez ist ein rîchiu kamere des hoehesten wîstuomes.ez ist ein vuore der hungeregen. ez ist ein labe der siechen. ez ist ein spunne der sûgenden kinde.ez ist ein tranc der vûlen inaedere der riuwenden. ez ist ein süezer stanc der muotsiechen. ez ist ein salbe der miselsuhtigen. ez ist ein ellen der vehtenden. ez ist ein lôn der sigehaften. ez ist ein widerladen der sigelôsen ze dem andern strîte.ez ist ein küele der müeden. ez ist ein mandunge der weinenden. (…) der ruowenden.ez ist ein umbehalsen des winelichen kusses. ez ist ein gezierde der kiuschen willen. ez ist ein wirdegiu corôna des magetlichen lebennes. lûte dich, heiteriu stimme, daz dich die unmüezegen vernemen. ganc her vür, süezer tôn, daz die vernemenden dich loben. hebe dich, wünneclicher clanc, daz dû gesweigest den kradem der unsaeligen welte.nû hebet iuch, heiligen noten der wünneclichen musicae. hebe dich ane, heiliger iubel des wünneclichen brûtsanges. kum, genuhtsamer tropfe des êwigen touwes, daz dû geviuhtest daz dürre gelende mînes innern menneschen.ganc durch den sin des ungehoerenden tôrn. | 6We have heard how the Holy Spirit spoke through wise Solomon when he expressed his wish for a strong woman. After that, he started to sing the cantica canticorum. Now let us see what kind of song that is. It is the song of all songs. It is also a vision of visible virtues. It is a pasture for the inner senses. It is a rich treasury of the highest wisdom. It is nourishment for the hungry. It is refreshment for the sick. It is a mother’s breast for infants. It is a healing potion for the rotten entrails of the penitents. It is a sweet fragrance for those sick at heart. It is an ointment for the lepers. It is strength for the fighters. It is a reward for the victorious. It is a re-invitation for the defeated to a new battle. It is a cooling for the weary. It is a joy for the weeping. It is a (…) for the resting. It is an embrace with a loving kiss. It is an adornment of chaste will. It is a worthy crown of the virginal life. Speak up, cheerful voice, so that the restless may hear you. Come forth, sweet tone, so that the listeners may praise you. Begin, delightful sound, so that you may silence the noise of the unfortunate world. Now begin, you holy notes of delightful music. Begin, holy jubilation of the delightful wedding song. Come, satisfying drop of eternal dew, so that you may moisten the dry land of my inner being. Go through the mind of the deaf fool. |

| 7kum durch den munt des unsprechenden stummen. kum durch den nebel des vinsteren ellendes, daz dîn lop sî von dannen, daz daz unverwarte sanc gê durch den verwarten munt. daz ich lop sage deme hoehesten briutegomen unde der heiligesten brûte. (…)daz ich mich menden müeze des kusses, dâ mit versüenet ist diu unsaelige welt. daz ich mich müeze menden, daz vergolten ist diu schulde wîpliches valles. daz ich mich mende, daz widere geladet ist daz verhundete her der verlornen sêle.nû genc ûf heiterer tac. dû rinnest ûf, heitere sunne des êwigen liehtes. schîn in die vinsteren kamere unser ellenden sêle, daz wir gevolgen müezen ze deme künneclichen gesidele dînes brûtstuoles, dâ diu diemüetege iuncvrouwe versüenet hât dich vater mit dînen kinden, dâ dâ geküsset ist diu kiuscheste brût, dâ dâ gehalsen ist diu reineste sêle der magetlichen muoter. danne hine vliehen die kleinen unt die tumben unt die kalten sinne. schrecken hine danne diu getelôsen kitze. rennen hine danne die ûf den olbenten sitzen.hie werden gerefset die ê genanten mägede ane die wârheit, die sich verdenet haben ane die stinkenden minne der vûlichen bôsheit. hie gevâhen rôten mit inneclicher schame diu hiufele, die sich flîzen der ûzeren schoene unde niht der inneren. smiegen sich diu kint des rîfen, sine gevalle ane daz tou der linden naht, oder siu beschîne daz lieht der heizzen sunnen. nû swîgen die vleischlichen unde niemen singe diz sanc âne gotes minne, wan den zerbrichet ez. nû komen alle unde menden sich sament die dâ gevlôhen habent den kradem der welte | 7Come through the mouth of the speechless mute. Come through the fog of the dark exile, so that your praise may happen when the unsealed song goes through the sealed mouth; so that I may praise the highest bridegroom and the holiest bride; (…) so that I may rejoice in the kiss with which the ill-fated world is atoned; so that I may rejoice that the guilt of Eve’s fall is repaid; so that I rejoice that the enslaved army of lost souls is invited again. Now rise, cheerful day. You run up, cheerful sun of eternal light. Shine into the dark chamber of our exiled soul, so that we may follow to the royal throne of your bridal chair, where the humble virgin has reconciled you, Father, with your children; where the chaste bride is kissed; where the purest soul of the virginal mother is embraced. May the weak and inexperienced and the cold senses flee away. May the unrestrained young goats be frightened away. May those who sit on camels hurry away. Here are to be chastened the aforementioned virgins to turn to the truth, those who have given themselves to the foul-smelling love of rotten wickedness. Here may the cheeks of those who strive for outer beauty, not inner beauty, blush with inner shame. Here may the children of the frost humble themselves before the dew of the gentle night falls on them or the light of the hot sun shines on them. Now let the carnal ones be silent and no one shall sing this song without the love of God. For it breaks somebody like that. Now let all come and rejoice together, who have fled the noise of the world |

| 8unde sich genomen habent von deme zarte der wolluste, unde die sich gevrîet habent vone der sorge weltlicher bürde. die menden sich mit mir des lieplichen KUSSES, dâ mite versüenet wart himel unde erde, engele unde menneschen.ÜBERGANG IN DIE AUSLEGUNG DES KUSSES VON CANT. 1,1Wir geben rehte unser genaedigen vrouwen die meisten êre dises sanges. wan siu diu êrste unde diu hêreste was, diu ie aller getriuwe–lîcheste GEKÜSSET wart. nû sehen waz daz KUS sî. got tet daz michel guot wider uns, dô er uns geschuof âne unsere gearnede. daz was sîn güete. er schuof uns ze sîneme bilde unde ze sîner gelîchnüssede, daz unser sêle sîn insigele waere. waeren wir volstanden, sône waere der MUNT, unser willen unde unser minne nie vone sîneme MUNDE genomen, daz sîn güete unde sîn genâde ist. dô wart daz insigele zerbrochen von deme êrsten wîbe unde gie dar nâch an allez menneschlichez künne unz an unser genaedigen vrouwen. daz was sunderigiu genâde, daz er wîbes val süende mit wîbes urstende. si vergalt Êve hôchvart mit ir diemüete unde was sô nidere, daz si der hoehste gereichen mahte. si was sô kiusche, daz si der schoeneste geminnen mahte. si was sô saelec, daz si der sterkeste gehalsen mahte. si was sô diemüete, daz si der hêreste erhoehen mahte. | 8and have withdrawn from the allure of lust and freed themselves from the concern of worldly burden. They may rejoice with me over the KISS of love that has reconciled heaven and earth, angels and humans. TRANSITION TO THE INTERPRETATION OF THE KISS FROM CT 1:1 Rightly, we attribute the highest honour of this song to our gracious Lady. For she was the first and the most exalted to be most loyally KISSED. Now let us see what the KISS means. God did something very good for us when he created us without any merit on our part. That was his goodness. He created us in his image and likeness so that our soul would be the imprint of his seal. Had we remained faithful to God, our MOUTH, our will, and our love would never have been taken away from his MOUTH, which is his goodness and his grace. The seal was broken by the first woman, and so it continued for all humanity until our gracious Lady. It was extraordinary grace that God reversed the fall of the woman with the exaltation of a woman. Eve’s pride was made good by her (Mary’s) humility. She was so lowly that the Highest could reach her. She was so chaste that the Most Beautiful could love her. She was so chosen that the Strongest could embrace her. She was so humble that the Most Exalted could elevate her. Therefore, no soul was ever so lovingly KISSED. The MOUTH with which she KISSED (her lips) were her will and her love. It was pressed (on his lips), on his goodness and on his grace. In KISSING, the MOUTH is closed; in speaking, it is opened. First, he KISSED her before he spoke to her. He was the KISSER who loved her. She was the KISSED who loved him. |

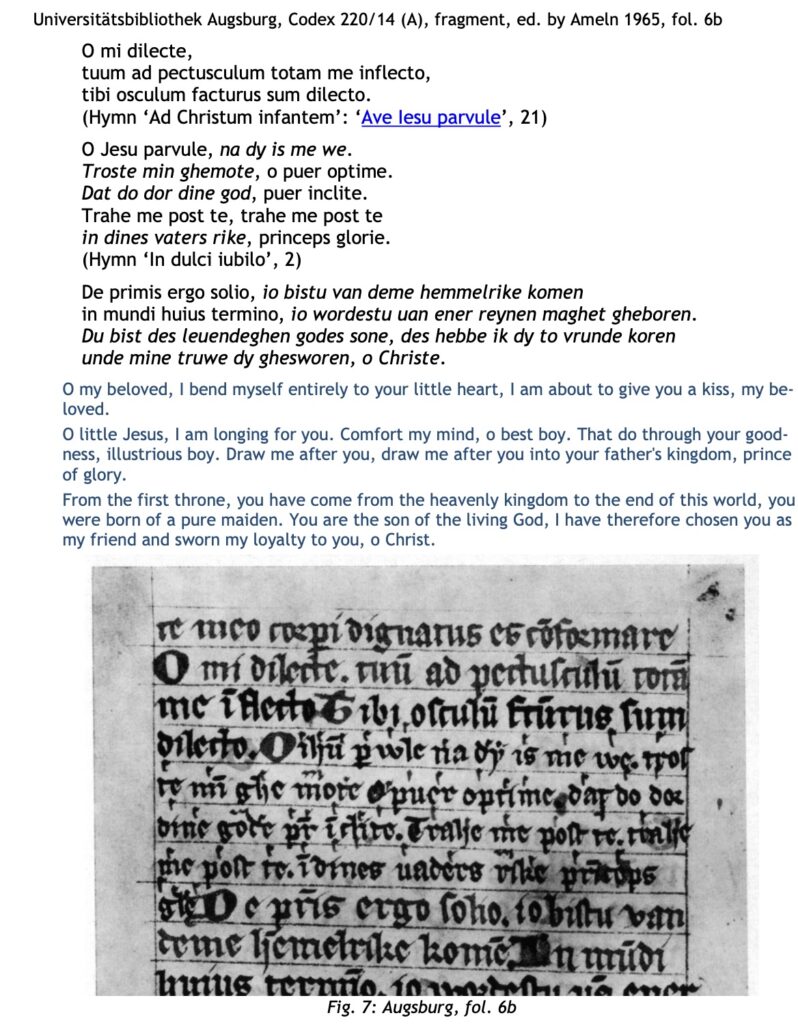

3. Medingen c. 1400: Christmas prayer book

4. Easter Prayer Book from Kloster Medingen, 1478

The Easter Prayer Book was written in 1478 by the nun Winheid (von Winsen?) in the Cistercian Abbey of Medingen, one of the Lüneburg convents which still exist today as Protestant female religious communities. The prayer book is a compilation and adaptation of the liturgy, hymns, older prayers, and vernacular poems. There was a tradition of compiling these prayer books at least since the late 14th century as a devotional exercise by nuns in the convent and also adding musical notation and illuminating the text with marginal illustrations. This copy is particularly elaborate and seems to have been written in preparation for a reform of the convent which took place in 1479 and led to an intensification of the devotional manuscript production. The manuscript is digitised here, as are many of the prayer books from the convent. Full information and bibliography on the blog medingen.seh.ox.ac.uk. The sigla of this manuscript, Dombibliothek Hildesheim Ms J 29 is HI1; other manuscripts I will discuss are K4, an Easter prayer book written by the Medingen nun Cecilia de Monte in 1408, and O1, an Easter prayer book started probably before the reform but extensively edited, now in the Bodleian Library in Oxford. I am currently working on a critical edition of the Hildesheim prayer book and both text and translation are taken from there.

5. Elisabeth Cruciger: Christological Hymn

The hymn by Elisabeth Cruciger, née von Meseritz, is published as part of the first Protestant hymnbook, the ‘Enchiridion oder Handbüchlein geistlicher Gesänge’ (Erfurt 1524). It was translated in the 1530s by Miles Coverdale into English as part of his ‘Goostly psalmes and spirituall songes’.

| Eyn Lobsanck von Christo | |

| Herr Christ der eynig Gotts son / vaters yn ewigkeyt / Aus seym hertzen entsprossen / gleich wie geschryben steht. 5 Er ist der morgen sterne / seyn glentze streckt er ferne / fur andern sternen klar. | 1. Christ is the only sonne of God the father eternall we haue in Iesse foude this rod god & man naturall he is the mornynge starre his beames sendeth he out farre beyonde other starres all. |

| Fur vns ein mensch geboren / ym letzten teil der zeyt / 10 Der mutter vnuerloren / yhr yungfrewlich keuscheyt. Den tod fur vns zu brochen / den hymel auffgeschlossen / das leben wider bracht. | 2. He was for vs a man borne In the last parte of tyme yet kepte she maydenheade vnforlorne his mother that bare hym He hath hell gates broken And heauen hath he made open Bryngynge vs lyfe agayne. |

| 15 Laß vns yn deiner liebe / vnd kentnis nemen zu / Das wir am glawben bleiben / vnd dienen ym geyst so. Das wir hie mugen schmecken / 20 deyn sussickeyt ym hertzen / vnd dursten stet nach dir. | 3. Thou onely maker of all thynge Thou euerlastynge lyght From ende to ende all rulynge By thyne owne godly myght. Turne thou oure hartes vnto the And lyghten them with the verite That they erre not from the ryght |

| Du Schepffer aller dinge / du vetterliche krafft. Regirst von end zu ende / 25 krefftig aus eigen macht Das hertz vns zu dir wende / vnd ker ab vnser synne / das sye nicht yrrn von dir. | 4. Let vs increace in loue of the And in knowlege also That we beleuynge stedfastly Maye in spirite serue the so That we in oure hartes maye sauoure Thy mercy and thy fauoure And to thyrst after no mo. |

| Ertödt vns durch deyn gute / 30 erweck vns durch deyn gnadt. Den alten menschen krencke / das der new leben mag. Wol hie auff dyser erden / den synn vnd all begerden / 35 vnd dancken han zu dir. | 5. Awake vs lorde we praye the Thy holy spirite vs geue which maye oure olde man mortifie That oure new man maye lyue So wyll we alwaye thanke the That she west vs so great mercye And oure synnes dost forgeue. |

Fig. 5: Enchirdion, Eyn Lobsanck von Christo

Fig. 6: Goostly Psalmes