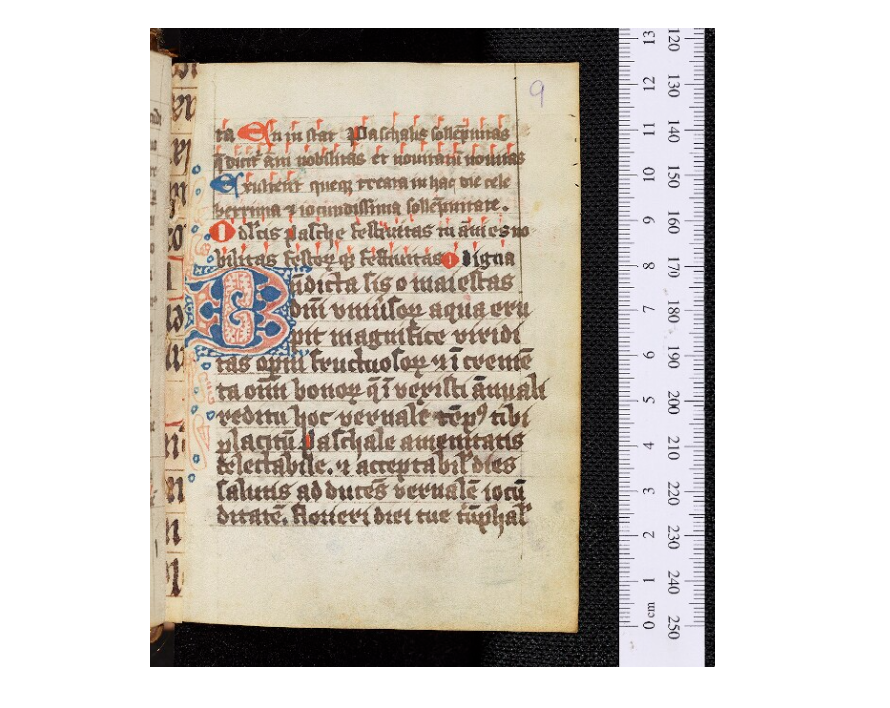

This folio offers a striking example of manuscript reworking at Medingen. The upper section, written in a smaller, later hand, was added over a palimpsest—apparently replacing an earlier text—while traces of the original, bolder script remain visible in the lower portion.

What happened to books when religious houses reformed?—Historians have long told a dramatic story: reform arrives, old books become obsolete, and manuscripts are discarded, sold, or cut up for reuse. Yet the surviving manuscripts from the Cistercian nunnery of Medingen, near Lüneburg, tell a far more nuanced—and far more interesting—story.

In my recent article in the Jahrbuch der Gesellschaft für niedersächsische Kirchengeschichte (2025), I revisit the manuscript culture of Medingen through the lens of the long fifteenth century. Rather than treating reform as a moment of rupture, I ask how books were reworked, reframed, and re-used by the nuns themselves—and what these material practices can tell us about religious change from within female monastic communities.

A Living Manuscript Tradition

Medingen is exceptional among the Lüneburg women’s convents for the sheer number of manuscripts associated with it: more than sixty-five survive today, scattered across collections in Europe and North America. Produced between the early fifteenth century and the mid-sixteenth century, these books—many written and illuminated by the nuns themselves—include prayer books, psalters, instructional manuals, and devotional compilations in both Latin and Middle Low German.

One manuscript stands out in particular: a small-format Easter prayer book completed in 1408 by the nun (and later prioress) Cecilia von dem Berge. Today preserved in Copenhagen (Ms GKS 3452-8°), this manuscript is the earliest securely dated book from Medingen. At first glance, it appears to be a finished, carefully planned object. A closer look, however, reveals something much more revealing.

Several prayers in this manuscript were later rewritten: earlier text was scraped away and replaced with new wording, written in a different hand and ink. These palimpsests are not accidents or signs of neglect. Instead, they point to a conscious engagement with existing devotional material—an effort to update, adapt, and realign texts with changing devotional priorities.

Reform as Reworking, Not Replacement

These material traces force us to rethink a familiar assumption: that reform meant discarding the old in favour of the new. In Medingen, reform often meant working with what already existed.

Rather than producing entirely new books, the nuns revised earlier manuscripts, overwriting, supplementing, and rearranging texts. This practice intensified in the later fifteenth century, particularly around the reform of 1479. Script, abbreviations, and layout all change, but the books themselves remain in use. Manuscripts thus became sites where continuity and change coexisted—objects through which reform was negotiated rather than simply imposed.

Such practices have often been overlooked because scholarship has tended to focus on newly produced manuscripts as evidence of reform. By paying closer attention to rewriting, palimpsests, and material reuse, we can begin to see how reform was lived and enacted on the page.

Women as Custodians of Tradition

This perspective also brings the agency of the Medingen nuns into sharper focus. With few contemporary narrative sources surviving from the convent itself, the manuscripts are among the most direct witnesses to the women’s religious lives. They show the nuns not as passive recipients of reforming ideals, but as active custodians of tradition—deciding what to preserve, what to revise, and how devotional practice should be shaped for their community.

Seen this way, the Medingen manuscripts challenge us to move beyond simple binaries of medieval versus early modern, Catholic versus Protestant, old versus new. Instead, they invite us to think about reform as a material process, unfolding gradually through books that were cherished, altered, and reused over generations.

The question, then, is not whether manuscripts were “given away, sold, or recycled,” but how rewriting itself became a powerful tool of religious transformation.

Want to Know More?

You can access the full article here: Gluchowski, Carolin, “‘Verschenkt, veräußert, vermakuliert?’ Die Handschriften aus dem Zisterzienserinnenkloster Medingen im Spiegel des langen 15. Jahrhunderts,” in Jahrbuch der Gesellschaft für niedersächsische Kirchengeschichte 123 (2025), pp. 91–128.