A Medingen Abbess As Owner of a Vernacular Sermon Manuscript?

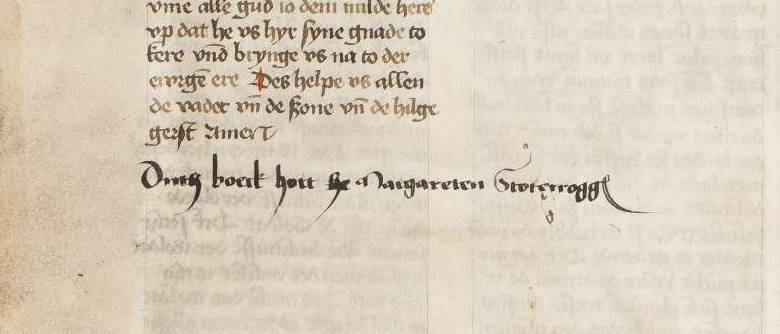

Duth boeck hort Margareten Stoterogge—“This book belongs to Margarete Stöterogge.”

On the last page of a fifteenth-century book of Middle Low German sermons, someone has written a brief note: Duth boeck hort Margareten Stoterogge—“This book belongs to Margarete Stöterogge”. At first glance it looks like a simple ownership mark. But the potential identity of this Margarete turns Lüneburg, Ratsbücherei, Ms. Theol. 2° 13 into an important source for Medingen’s religious history. One of three women named Margarete Stöterogge, daughter of the Lüneburg mayor Hartwig Stöterogge, became abbess of the Cistercian convent of Medingen in 1524 and remained in office until her death in 1567. Her time as abbess covers the long shift at Medingen from a reformed late-medieval convent to a Lutheran community.

A North German Sermon Codex that “Arrived”

Ms. Theol. 2° 13 is a 15th-century parchment manuscript of 188 leaves, measuring roughly 29.5 × 21 cm, copied in a single hand in two columns of thirty-six lines, using a Gothic set script for the Latin incipits and Bastarda for the Low German body of the text: sturdy, legible, and functionally designed.

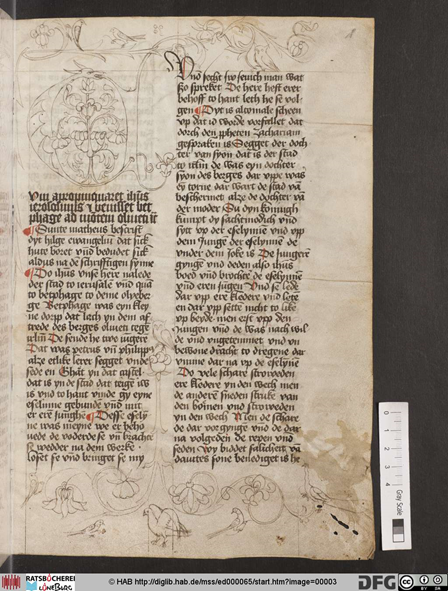

The only pen drawing at the start (fig. 2) was never illuminated. The ten-line initial dragon-like letter C twists into foliate scrolls, with columbine tendrils populated by birds running into the margin. After this, the book shows only red and blue lombard initials, rubricated headings, and minimal paratextual cues that allow the reader to navigate the sermon sequence quickly and reliably.

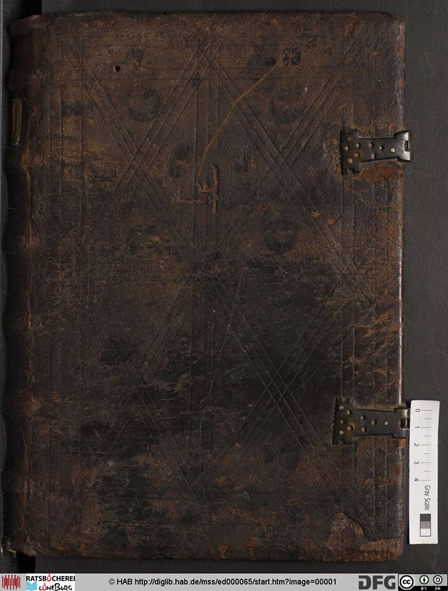

The binding (fig. 3) consists of late-medieval wooden boards covered in brown leather, fitted with two clasps, while the rear pastedown from a recycled fragment of Eberhard of Béthune’s Graecismus (d. c. 1212). This situates the volume within a monastic book culture of durability, legibility, and reuse.

If this was once in Medingen, it does not look like the “house style” of the Medingen prayer books (fig. 4): small-format volumes, densely but delicately decorated, combining Latin texts with Middle Low German prayers and songs, often written by the nuns themselves after the 1479 reform, making them instantly recognisable. Ms. Theol. 2° 13 thus probably arrived at Medingen as a gift from another religious house or person. The language, format and decoration fit comfortably alongside other Lüneburg-region sermon and theology manuscripts preserved from male houses such as the Franciscan convent or St Michaelis.

Sermons, Vernacular Devotion, and the Long History of “Reform”

Content-wise, Ms. Theol. 2° 13 contains a cycle of Middle Low German Sunday sermons arranged by Gospel incipit through the church year, concluding with a prayer. We know that abbesses preached on the nuns’ choir and sermon collections offered preparation for this. It could be read during communal reading, or help prepare own sermons. A Middle Low German sermon collection in the 1520s–1550s disrupts any neat “Latin before / Low German after” narrative of the Reformation but convent’s books became battle grounds in the early 1530s, when ducal theologians scrutinised and selectively “reformed” the nuns’ manuscripts, erasing or revising invocations of saints and other contested devotional elements. If control over which texts—and in what form—circulated was a key technology of governance in the Reformation decades, then an ownership claimed guardianship over a specific way of mediating Scripture and doctrine.

The Abbess Behind the Inscription

The Stöteroggen family was influential. In 1504, Hartwig Stöterogge, with his wife’s consent, endowed Medingen with an annual rent of twenty-four Mark in return for the admission of his daughters Katharina and Margarete. When Margarete was elected abbess in 1524, she entered office just as ducal reform pressure intensified. She wrote a number of letters to Lüne, e.g. in a letter of 26 September 1525 (Lüne letter no. 13) she reports Duke Ernst’s attempt to impose his new church order on the community: the sisters resisted under interrogation, but were compelled to accept the compilation and submission of a detailed inventory of the convent’s goods. The result was not a clean victory for either side but a protracted, negotiated compromise. Through the mediation of Margarete’s brother Nikolaus, a councillor and later mayor of Lüneburg, Medingen gradually adopted key Lutheran practices while preserving significant elements of its communal identity and material foundation. until she received communion in both kinds in 1554.

Custody in Ink

Taken on its own, Duth boeck hort Margareten Stoterogge could be dismissed as a routine provenance note, the sort of scribble catalogues record and then pass over. Set within the codicological, devotional, and political contexts of late fifteenth-century North German when the region’s confessional future was being renegotiated, it situates a Middle Low German sermon collection within a long-standing vernacular culture that the Reformation sought not so much to introduce as to discipline.

If we read the ownership note as an act of custody rather than a mere label, Ms. Theol. 2° 13 becomes a hinge between late-medieval reform and early modern confessionalisation. It shows an woman claiming not only a physical object, but a particular way of hearing, reading, and teaching the Gospels at a moment when those practices were under scrutiny. It offers a small but suggestive case study of how women religious could inscribe their agency into the very margins—and final pages—of the books through which reform was contested.